Bob Audette, Brattleboro Reformer

December 22, 2021

BRATTLEBORO — “We need support that’s free from coercion, force and barriers,” stated one participant quoted in Brattleboro’s Community Safety Report, which recommends a decoupling of mental health crisis response from law enforcement.

“Police participation in mental health interventions increases the use of unwanted harmful practices instead of support, including coercion, threats, intimidation and force in systems response to mental and emotional health crises,” states the report, which was presented to the Select Board a little less than a year ago.

Recently, at its last meeting, the Select Board set aside $200,000 for a new community safety fund to establish alternatives to traditional policing. Another $100,000 has been suggested for the fund for the next fiscal year, which begins on July 1, 2022.

Town Manager Peter Elwell said the $200,000 comes from the salary line in the police budget, because the department is understaffed, with just 18 officers and room for nine more.

Elwell said the community safety fund is intended for “small-scale, community-based initiatives” organized by regular citizens with innovative ideas that could lead to a decoupling of mental health response from law enforcement.

A model for the town is already available and has been providing front-line help to people in the community for more than five years.

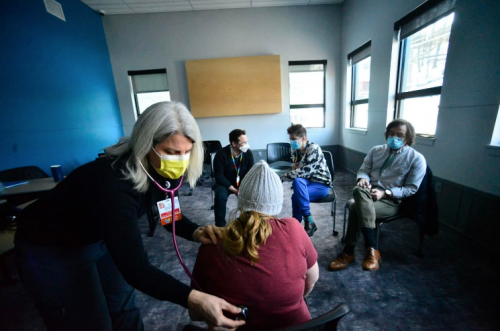

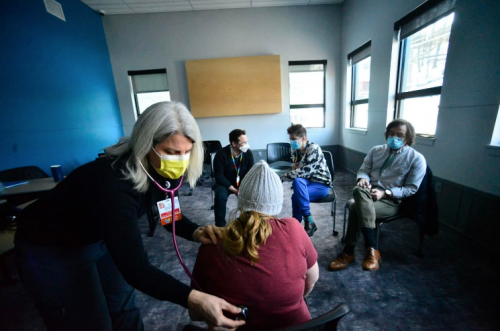

Healthworks, at Groundworks Collaborative, provides support to families and individuals facing housing and food insecurities in the greater Brattleboro area.

The Healthworks team consists of a licensed mental health clinician from the Brattleboro Retreat, a vulnerable population care coordinator from Brattleboro Memorial Hospital who is a registered nurse, and a case manager from HCRS (Healthcare and Rehabilitation Services).

The program serves as a bridge between folks with all sorts of mental and medical health needs and care providers in the community, said Rhianna Kendrick, director of operations at Groundworks.

“We often are supporting folks with really challenging, complex needs,” said Kendrick, describing Groundworks as “the final safety net.”

Many of those people have also experienced trauma and the law enforcement response that comes along with it.

“Police don’t represent a positive response to folks that we serve, typically,” she said.

And while law enforcement has a role to play in responding to emergencies, Kendrick said, “Police should not be the response to a mental health crisis or an overdose or somebody’s medical crisis.”

Kendrick is appreciative of the work police do in the community, but she noted that in the majority of mental health crises, violence is extremely rare.

Kate Lamphere, adult services division director for Health Care and Rehabilitation Services, said there is a role for police in responding to certain medical or mental health calls.

“For years, we’ve been doing the co-response model,” she said, “but I also think there is an opportunity for a different response that doesn’t include law enforcement.”

In addition to its collaboration with Groundworks, HCRS has a crisis team that can meet people in its offices, in an emergency room or in some other safe setting.

“Our average response time is just shy of 30 minutes, though we can do telemedicine in zero minutes,” Lamphere said. Unfortunately, she said, some face-to-face responses, depending on the time of day, can take hours and law enforcement is often the first on the scene for those calls.

“We’d prefer a model where law enforcement doesn’t have to be involved in any mental health response,” she said.

Brattleboro Police Chief Norma Hardy said she welcomes the discussion.

She said the department has been in ongoing discussions with everyone involved with the Healthworks team.

“We are trying to find better ways of policing while protecting the community at the same time,” Hardy said.

With a mental health response team in place, she said, police can focus on crimes like drug dealing and human trafficking, both of which are serious problems.

“If we can all come together with something everybody has a part of, it will work out even better,” Hardy said.

In Windham County, HCRS’ crisis team has two staffers during the day, Monday through Friday, and one staffer on every other shift.

“That sure does limit the response time,” said Lamphere, noting it’s more about finding the right people rather than finding the money to staff a true 24-hour response team.

“There’s room to support a more robust community response, but we are struggling with a staffing crisis just like every other entity.”

Much of the time, the team is dispatched to an emergency department, which is not the best place to treat a mental health crisis because it often includes confinement.

But the team can also respond to a home, especially when someone doesn’t want to go to the emergency room or go with law enforcement anywhere.

“Being able to respond to people in places where they feel safe is a big departure from how mental health support has been provided,” Kendrick said.

Kurt White, the senior director for outpatient programs and community initiatives at the Brattleboro Retreat, said the Healthworks Program has been a remarkable success, working with people before a crisis can develop into a public emergency that requires a police response.

But replacing a police officer with a social worker makes him “a little nervous,” he said.

“There are two things in any kind of crisis situation you have to tend to,” he said. “First, make sure everyone is safe, and second, deescalate the situation. Sometimes those two things can be in conflict. The police can be a wonderful tool for sorting that out.”

But White agrees with Lamphere and Kendrick that the best response meets people where they are, either at home or some other safe place.

“There’s a spectrum of intervention and response,” White said, which doesn’t necessarily include a hospital emergency department where someone might have been “escorted” by police.

“An emergency room can be as hectic as Logan Airport during the holiday season,” he said, which is not good for anyone’s mental health.

The next step for Healthworks is to transition to what is called “an action crisis treatment team,” White said, which is an evidence-based model for intervening with people with high needs.

“We are actively seeking funding for a pilot project,” he said.

Matthew Dove, nurse practitioner and the Brattleboro hospital’s behavioral health resource coordinator in the emergency department, said assertive community treatment teams are evidence-based models that have proven track records.

Dove said models like Healthworks and community action response teams can reduce dependency on emergency departments. This is not only important in addressing a person’s needs, but also in keeping the emergency department available for medical emergencies, especially during a pandemic.

Kendrick also emphasizes the importance of peer support in a crisis. With more funding and people who want to do the work, she said, Groundworks could provide 24/7 support services, but that would be specific to the demographic the organization serves, not the community at large.

“The HCRS model works great for some of the folks who need them,” Kendrick said. “But it doesn’t quite extend to everyone.”

HCRS is also considering a crisis response model that includes people “with lived experience” who can provide support to community members that limits the need for a police response.

“With adequate funding for community mental health, we can prevent a crisis in the first place,” Lamphere said.

***

Photo Credit: Kristopher Radder, Brattleboro Reformer